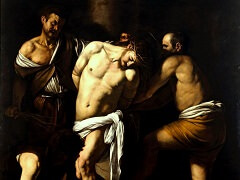

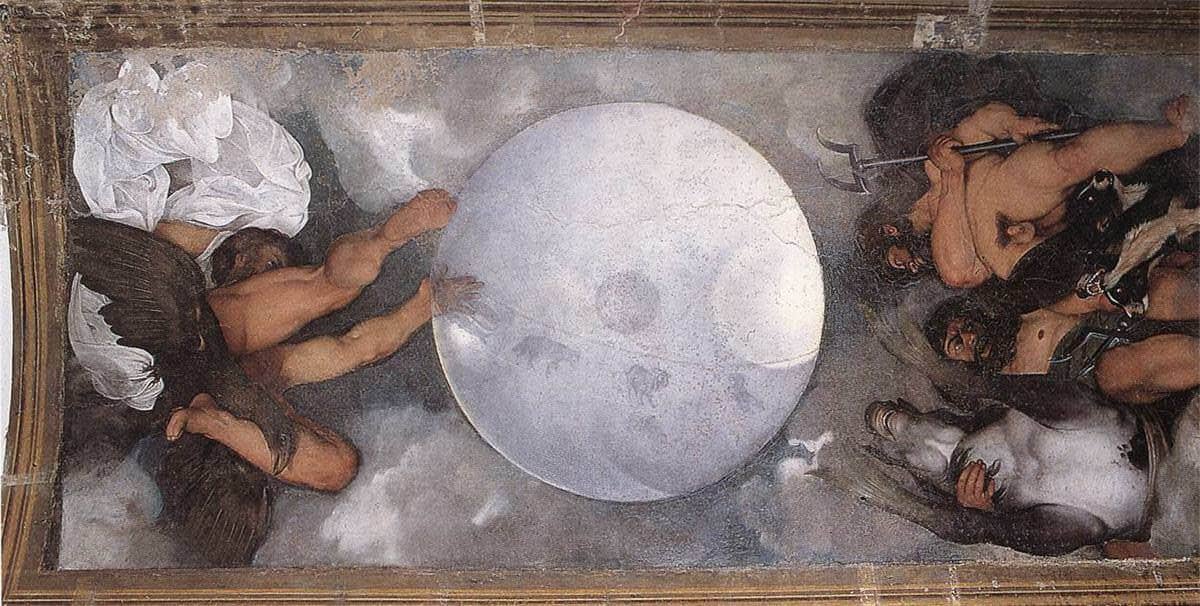

Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto, 1597 by Caravaggio

Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto was ignored until 1969, when an Italian scholar rediscovered it, and critical opinion of it is still divided.

Cardinal del Monte bought the villa on November 26, 1596, and occupied it a month later. Probably Caravaggio painted the ceiling during the following months. The cardinal sold the villa to the Ludovisi family in 1621, and it was

remodeled and redecorated.

Cardinal del Monte's principal laboratory was in the Palazzo Madama. This room in the villa was probably his private study, where he might have been more willing to permit his protege to attempt his first - and, as it turned out,

only - ceiling decoration. The telltale outlines incised around the figures betray their origin in the fresco technique. Perhaps the attempt to paint in oil on stucco was Del Monte's idea, inspired by

Leonardo da Vinci's efforts in The Last Supper in Milan. Solving the technical problems would have appealed to the

cardinal's interest in chemistry, and, in fact, despite some losses the ceiling has survived three centuries of neglect surprisingly well.

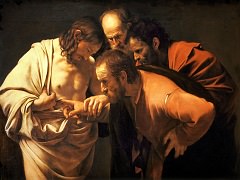

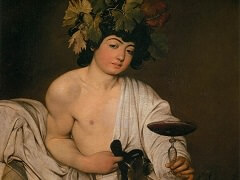

In this painting, Caravaggio was clever enough to have created this likeness consciously. It is no less convincing stylistically: the compact masculinity of the figures is defined by the same unbroken outlines and the same

anatomical generalizations as in the Bacchus. Neptune is easily recognizable as Bacchus's bearded older brother, no less for his plump, rather effete hand than for his distinctive nose and arched eye-brows. The bits of white

drapery scattered over the ceiling might literally have been cut from the same bolt of cloth as the white stuffs in the Bacchus; certainly they fall into the same patterns of convoluted folds.

The perspective effects, lacking any architectural point of reference within the painting, are daring but not unexpected in a showpiece by a cocky young artist. Perhaps Caravaggio was helped by the cardinal's brother Guidobaldo,

who wrote a distinguished treatise on perspective. He surely made use of prints of earlier sixteenth-century perspective ceilings, notably Giulio Romano's in the Palazzo del Te, Mantua.

Cardinal del Monte believed all natural things to be derived from a triad of elements: sulphur-air (Jupiter), mercury-water (Neptune), and salt-earth (Pluto). In the painting, Jupiter, floating on top between his two brothers, is

manipulating a celestial globe containing the earth, the sun, and the stars, in order to achieve the astrological conditions propitious for the processes that Paracelsus called the Great Work, whereby the three elements could be

transformed into the philosopher's stone, that is, the elixir of life. The philosophical implication is that by mastering the elements and therefore the material world, man might also control his own spirit, surely an appropriate

sentiment for the private study of a learned sophisticate like Del Monte.