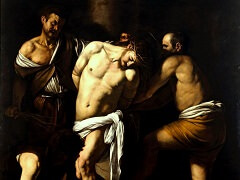

Bacchus, 1596 by Caravaggio

Despite recent scholarly efforts to establish the Bacchus as an allegory - of the sense of taste, or even of Christ - the painting remains sufficient and convincing as simply the portrayal of a boy dressed as the ancient god of wine.

It is less a satire than a kind of living symbolism.

It is Caravaggio's first obviously classical work. The boy is a muscular ephebe, lolling on a lectus, an ancient couch, and dressed not in the flimsy shirt of a contemporary musician but in heavier stuff, reminiscent of the carved

drapery in ancient Roman sculpture. His hair, surely a wig, is crowned with a wreath of black and white grapes and their leaves, and he offers the viewer a glass kylix of red wine, the cup of pleasure. Caravaggio's inspiration was

one of the many surviving statues of the Emperor Hadrian's beloved, Antinous, who was often represented as Bacchus; perhaps it was the full-length statue of the god that belonged to the Marchese Giustiniani, and was engraved about

1630. The pose seems derived from a frescoed Bacchus painted by Federico Zuccaro during 1584-85 in a lunette in the studio of his house in Florence

The objects on the table are palpable under natural light which, however, casts no shadow on the background. The illusion is as seductive as the boy himself. He offers not only wine but himself as well: his right hand toys with

his sash, which barely holds his drapery together. The image is a kind of imposture: the pose and costume, the affected coiffure, plucked eyebrows, pudgy hand, and plump hairless body are betrayed by the disturbingly muscular arm

and the sullen provocative expression.

Someone may have dictated to Caravaggio devices to transfigure the paganism of the image into concealed Christian symbolism. Knowledge of some such signification may have made the picture acceptable to connoisseurs. But what Caravaggio characterized was a body dedicated to sensuality rather than a soul infected with Christianity. The sly, dreamy eyes speculate on carnal things and promise gratification of the senses, not of the spirit, as "love cools without wine and fruit." Yet the possibility of an underlying moral, bizarre as it may seem and contradicted by appearances, cannot be totally ignored. The touches of corruption in the still life - the wormhole that has spoiled the apple, the pomegranate that has burst from overripeness - hint again of the Vanitas theme, that the boy is triumphant only in his youth, which will vanish as quickly as the bubbles in the carafe of freshly poured wine.