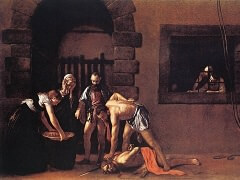

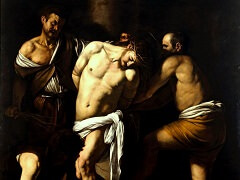

The Crucifixion of St. Andrew, 1607 by Caravaggio

St Andrew was patron saint of Constantinople. From that city his body had been snatched by crusaders and brought to Amalfi, just one bay south of Naples. The Count of Benevente, viceroy to Philip III, King of Spain, was charged by his royal master to renovate the crypt in the cathedral of Amalfi, where the saint is buried; and it must have been while he was so engaged that he asked Caravaggio to paint him the scene of the saint's death. The painting was in the v iceroy's grandson's inventory in 1653, then disappeared for over two centuries till it was bought from a private Spanish collection.

It was customary to show Andrew crucified on a cross formed by two diagonals. According to the The Golden Legend, Aegeas, the proconsul of Patras, had Andrew held on the cross by ropes rather than nails, to prolong his suffering. But Andrew took advantage of his slow death to preach from the cross for two days, till the people threatened violence unless he were taken down. By this time Andrew had preached enough and, to die quickly, prayed that his limbs would be paralysed so that he could not be cut down. As a great light shines, he dies.

It is this moment that Caravaggio paints. The old man looks weary from his agony, and the sturdy executioner who tries to undo the thongs is twisted round in a vain attempt to release him. Below a small group are transfixed by Andrew's eloquence: an old woman with a goitre (Andrew cured throat infections), a knight in black shining armour (the sceptical Aegeas), a middle-aged man and, behind the knight, a young bravo. By restricting any sense of space Caravaggio has made a drama more intimate than the events of everyday life.