The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1600 by Caravaggio

The subject traditionally was represented either indoors or out; sometimes Saint Matthew is shown inside a building, with Christ outside (following the Biblical text) summoning him through a window. Both before and after Caravaggio

the subject was often used as a pretext for anecdotal genre paintings. Caravaggio may well have been familiar with earlier Netherlandish paintings of money lenders or of gamblers seated around a table like Saint Matthew and his

associates.

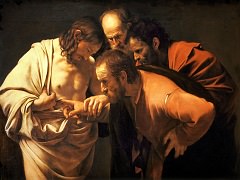

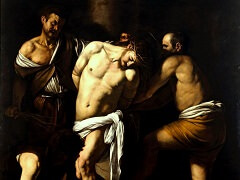

Caravaggio represented the event as a nearly silent, dramatic narrative. The sequence of actions before and after this moment can be easily and convincingly re-created. The tax-gatherer Levi (Saint Matthew's name before he became

the apostle) was seated at a table with his four assistants, counting the day's proceeds, the group lighted from a source at the upper right of the painting. Christ, His eyes veiled, with His halo the only hint of divinity, enters

with Saint Peter. A gesture of His right hand, all the more powerful and compelling because of its languor, summons Levi. Surprised by the intrusion and perhaps dazzled by the sudden light from the just-opened door, Levi draws

back and gestures toward himself with his left hand as if to say, "Who, me?", his right hand remaining on the coin he had been counting before Christ's entrance.

The two figures on the left, derived from a 1545 Hans Holbein print representing gamblers unaware of the appearance of Death, are so concerned with counting the money that they do not even notice Christ's arrival; symbolically their inattention to Christ deprives them of the opportunity He offers for eternal life, and condemns them to death. The two boys in the center do respond, the younger one drawing back against Levi as if seeking his protection, the swaggering older one, who is armed, leaning forward a little menacingly. Saint Peter gestures firmly with his hand to calm his potential resistance. The dramatic point of the picture is that for this moment, no one does anything. Christ's appearance is so unexpected and His gesture so commanding as to suspend action for a shocked instant, before reaction can take place. In another second, Levi will rise up and follow Christ - in fact, Christ's feet are already turned as if to leave the room. The particular power of the picture is in this cessation of action. It utilizes the fundamentally static medium of painting to convey characteristic human indecision after a challenge or command and before reaction.

The picture is divided into two parts. The standing figures on the right form a vertical rectangle; those gathered around the table on the left a horizontal block. The costumes reinforce the contrast. Levi and his subordinates,

who are involved in affairs of this world, are dressed in a contemporary mode, while the barefoot Christ and Saint Peter, who summon Levi to another life and world, appear in timeless cloaks. The two groups are also separated by

a void, bridged literally and symbolically by Christ's hand. This hand, like Adam's in Michelangelo's Creation of Adam,

unifies the two parts formally and psychologically. Underlying the shallow stage-like space of the picture is a grid pattern of verticals and horizontals, which knit it together structurally.

The light has been no less carefully manipulated: the visible window covered with oilskin, very likely to provide diffused light in the painter's studio; the upper light, to illuminate Saint Matthew's face and the seated group;

and the light behind Christ and Saint Peter, introduced only with them. It may be that this third source of light is intended as miraculous. Otherwise, why does Saint Peter cast no shadow on the defensive youth facing him ?