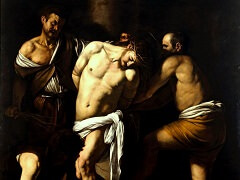

The Conversion of Saint Paul, 1600 by Caravaggio

Only Baglione mentions that Caravaggio carried out two sets of paintings for the Cerasi Chapel. He wrote that the first pair was rejected because the donor, Monsignor Cerasi, did not like them (therefore they must have been

completed before Cerasi's death in May, 1601). Baglione had good reason to hate Caravaggio, so his statement may be suspect, particularly when unconfirmed by any other source as close to the scene as he was. Mancini was that close,

and his only relevant comment is that Cardinal Sannesio owned pictures that were "copied and retouched" from those now in the chapel, a description surely not applicable to this painting. It is not specifically documented until

1701, when it was in Genoa bequeathed by Francesco Maria Balbi, from whose heirs it eventually passed to Prince Odescalchi. Many Caravaggio specialists have not felt able to place so crowded and confused a

composition anywhere in Caravaggio's oeuvre.

However, Baglione does write that Caravaggio painted the first set in a manner different from his usual style. The intricately packed composition, which by itself seems so contradictory, is remarkably similar to the tangled left

side of the final version of The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew, which should have immediately preceded it chronologically. The source of light from the right, as in the final version, would

be exceptional in Caravaggio's oeuvre, but correct for the painting if it were installed on the right wall of the chapel. The support, the cypress-wood panel required in the contract, is only slightly smaller than the canvas now in place.

The old bearded soldier, Christ, and the boy angel are familiar Caravaggio models, and the landscape is similar to that in The Sacrifice of Isaac. Finally, whatever questions have been

raised about this picture, the brilliant/attura is undeniably worthy of Caravaggio himself; virtuoso details such as the helmet or the old soldier's sleeve require a hand as skilled as his.

The vision is described by Saint Paul himself in Acts 22: 5-11 as a great light at midday that struck him blind while he was en route to Damascus to prosecute Christians. Traditionally painters have represented this scene as a

dramatic, even terrifying, divine intervention in the affairs of man, manifest to Saul and his companions by the appearance of Christ in the heavens. A rearing horse and an alarmed soldier are customary; the pose of Saul's body

may well have been consciously derived from Michelangelo's Pauline fresco. I doubt that Caravaggio meant to suggest that anyone actually saw Christ. The soldier's response could be to only the light flooding over his head and over

Saul's body. Instead, I believe that by giving Christ and the angel visible form Caravaggio meant to imply the voice that Saint Paul heard saying, "Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?" The message is conveyed eloquently by

Christ's arms, extended beseechingly rather than commandingly.