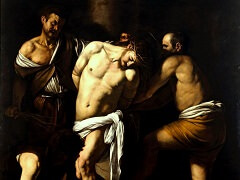

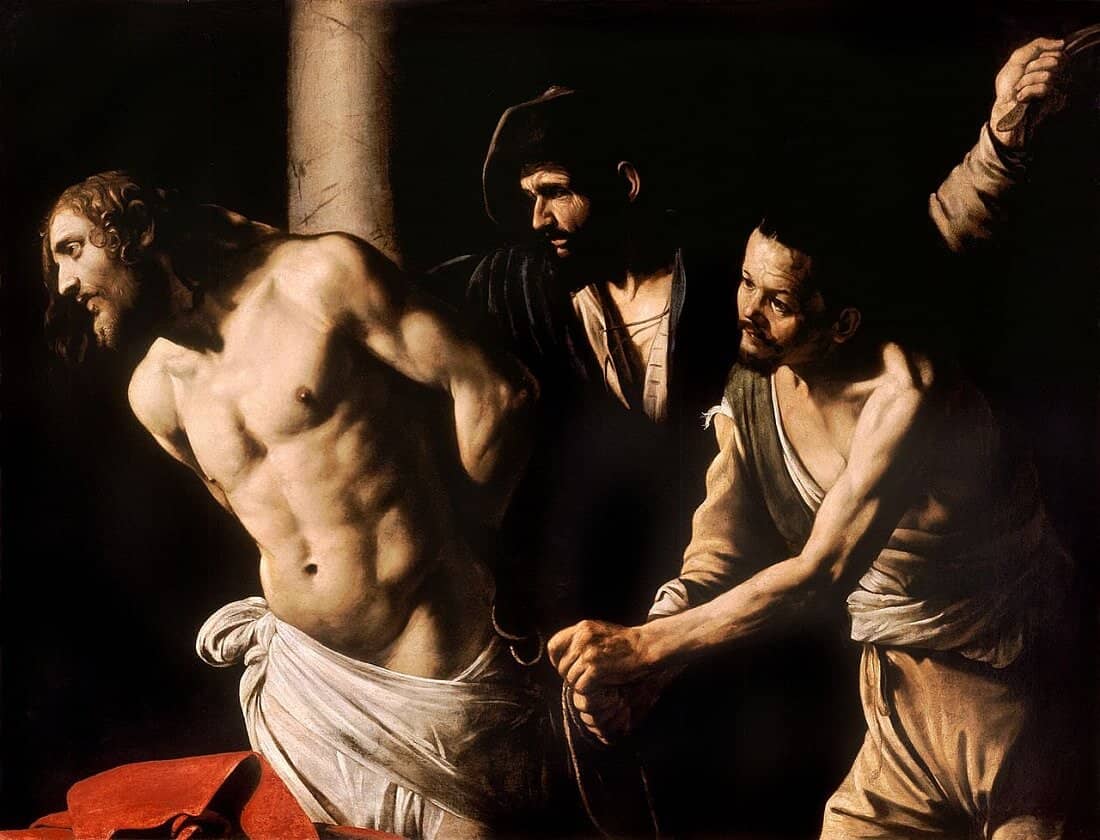

Christ at the Column, 1607 by Caravaggio

Christ at the Column is one of two versions of the Flagellation of Christ by Caravaggio. The painting shows the flagellation of Christ following his arrest and trial and before his crucifixion. The

scene was traditionally depicted in front of a column, possibly alluding to the judgement hall of Pilate.

In late 1609 Caravaggio was in Naples again and suffered an attempt to his life. He was severely wounded in the face by a knife's stab. He tried to return to Rome by boat, but was arrested by Spanish soldiers yet liberated rapidly.

He set out on foot for Rome, maybe to catch another ship further on the coast, and died on a beach near Naples from a fever. It remains unclear whether he died of fever or was reached by soldiers of the Pope or by a wronged Knight

of Malta, and murdered

Caravaggio's roots and affinities lay deeply with the Italian people of the alleys of Rome and Naples. He opposed the artificial compositions and mannered expression of emotions with the realism of immediate sense. He painted

natural poses and his figures were very dynamic, very lively and very present in his compositions. To the pure colours of the Florentine Renaissance he opposed more sombre tones and he introduced prominently the contrast between

light and dark. The Florentines had used shadows since always, but Caravaggio constructed his figures out of the conflict between light and absence of light. Stating that Caravaggio used sombre tones and introduced the contrast

between dark and light in the visual arts is however an inadequate description of the genius that he was.

Caravaggio painted his Christ at the Column in Naples in 1606-1607, just after he had left Rome. He was bewildered. He had participated in killing a man; he probably had killed the man himself. His conscience tore at him,

to the right and to the left, but he could not escape the image in his mind. Such also is the image of Jesus at the column. Jesus tears aside of the column, but his hands are tied and kept to the marble by a soldier of Pilate.

Suffering cannot be escaped from, as a conscience cannot be escaped from. A soldier grasps Jesus' hair and holds the whip high, ready for the next lashing. All is intense movement in this picture, caught on the canvas in the spur

of the moment.

Jesus reclines to the left. He does not stand upright as in al the paintings of previous Italian artistic periods and styles. Jesus is naked, showing a powerful muscular body. He is not the young idealised, even slightly

androgynous, Renaissance youth anymore. The other figures of the paintings are also drawn in oblique directions, leaning to left or right. Caravaggio favoured diagonals. But balance and the vertical dimension had to be added to

give the viewer a line of reference besides the frame. Therefore there is the column. The column of the Praetorium is in the title of the picture. It has become the one element of stability that we are familiar with. Here we find

pure genius at work. Once stability and the line of reference were established, Caravaggio could represent the figures in swift movements and unusual angles. The picture seems easy and natural, but Caravaggio broke with all

academics and styles with Christ at the Column.