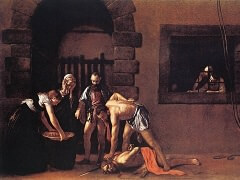

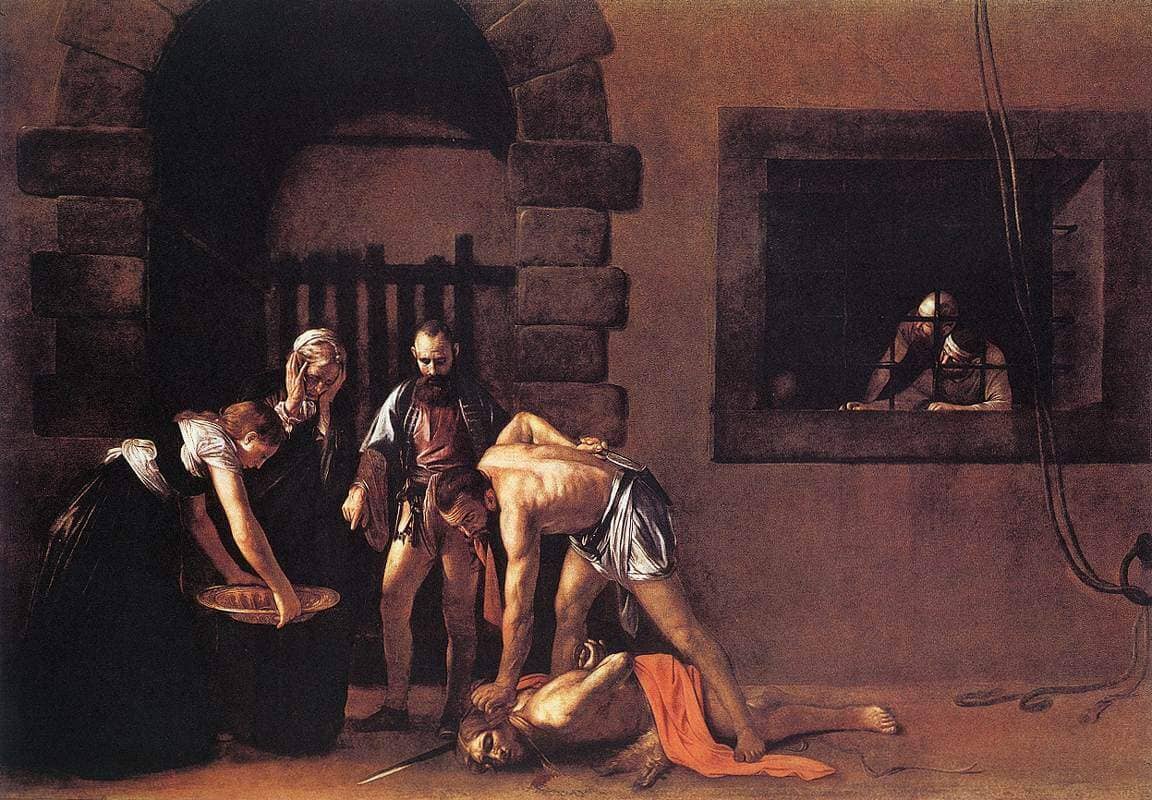

The Decapitation of Saint John the Baptist, 1607 by Caravaggio

Saint John was the patron saint of the Knights of Malta and of the cathedral, for the new oratory of which Caravaggio painted this canvas. It is his largest work, and the only one he signed - prophetically, in the blood flowing onto the pavement from the saint's neck. The Grand Master was so pleased by it, according to Bellori, that he presented Caravaggio with a gold chain, two slaves, and various other rewards; the frame bears his coat of arms. Bellori's implication that it was painted after the portrait of Wignancourt is unreliable.

The structure recalls the monumental murals that Caravaggio must have studied in Rome. No specific detail seems to be derived from them, but we can sense their reverberation - notably The School of Athens by Raphael in the combination of circular forms with horizontals, the ample space, and the integration of the figures and the building. This building is Caravaggio's most detailed architectural setting, and the only one that records an existing structure, the entrance and adjacent window in the main facade of the Grand Master's Palace (now the Armory) in La Valletta.

The composition is classically simple, a large shallow space with a cluster of figures on the left balanced by a wall and a window on the right. It is held together by a series of horizontals, most obvious the base line of the wall and the line formed by the extension of the tie rod to the upper edge of the window. Caravaggio's palette was so muted, and the density of the atmosphere is so great - only the spotlight on the figures penetrates it - that the two-dimensional effect is of a single vast color field with accents placed on it.

The dramatic impact of the composition almost obliterates its effectiveness as an abstract construction. It is a silent painting, intimate despite its great scale. The focus is first on the pointing index finger of the business-like warden, who forms the single vertical axis in the figure group, directing the operation. Only secondarily can Saint John's body be found. It is over-lifesize, and the only horizontal figure. From the center of the warden's finger, the action fans out - to the executioner's left hand, holding Saint John's partially severed head in place like a butcher in an abattoir while he reaches with his right for his dagger to finish the process off neatly; to the platter, held low by Salome in anticipation of receiving the head; to the old woman. She is horrified, the only character responding sympathetically to the execution. Incredibly, she covers her ears rather than her eyes; are the sounds - those of the actual decapitation - worse than the sight? Or is this, like so many other gestures in Caravaggio's oeuvre, kinesthetic - is she making us aware that if we can see, we can also hear? Perhaps Caravaggio intended to stimulate a similar sense of projection in the poses of the two spectators, straining on our behalf as much as their own, curious to see what is happening. Finally, we must allow - or force - ourselves to look past the deadly line of the glittering blade at the pathos of Saint John's painfully bound body. A moment before he was a seeing, hearing, feeling, thinking human being like the others; now he is reduced to a mere fleshly carcass.