The Sacrifice of Isaac, 1602 by Caravaggio

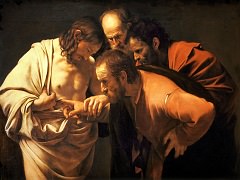

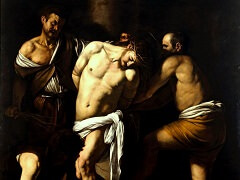

Although the pair of figures barely discernible in the right background may refer to the two young men who accompanied Abraham but were left at the foot of the mountain to wait while he sacrificed his son, other details do not follow the account in Genesis 22 precisely. According to the Biblical text, Abraham prepared for a burnt offering, laying Isaac bound on a pile of wood on an improvised altar. Just as Abraham was about to slay his son, an angel intervened by calling to him. A ram then unexpectedly appeared, divinely provided as a substitute sacrifice for Isaac. In Caravaggio's visualization of the subject, the angel physically materializes beside Abraham. This treatment of the subject was customary, and Caravaggio took full advantage of its potential for drama.

It is another of his favored crucial moments between one course of action and another abruptly superseding it. Abraham has laid Isaac down on the altar, drawn the knife, and is at the point of slitting his throat; the restraining angel rushes urgently to the rescue just in time. The focus of the action is on the patriarch's right hand holding the knife. The three heads are radial to it, and it joins the authoritarian figures on the left to the victims on the right. The other hands are hardly less expressive: the angel's left with its commanding gesture and Abraham's left grasping his squirming son to steady him. The concealment of Isaac's hands emphasizes his helplessness.

Monsignor Maffeo Barberini's agents paid Caravaggio for this painting and perhaps another that has not been identified, in four installments, the first in May, 1603, and the last in January, 1604. The precision of this documentation provides a key to Caravaggio's chronology and evolution. The frieze-like composition he adapted from his own Judith, reversing the sequence of action to read from left to right. But during the five intervening years the figures have become more fully three-dimensional, and the space adequate to permit them to move freely within a single frame of reference. Abraham is the same model as the background apostle in the Incredulity and as the second Saint Matthew. The light on the angel and the modeling of his body make him the Capitoline Youth's unsullied brother; without the clue of his wings, he would seem as mortal, and his nudity and his capability to interfere with the implacable Abraham would be inexplicable. The terrified Isaac is Caravaggio's naughty little friend, the Amor, no longer victorious and now a couple of years older. Parenthetically, can we read the image as a playfully sarcastic intimate threat to the boy?