The Taking of Christ, 1602 by Caravaggio

Throughout history, very few artists have caused as radical a change in pictorial perceptions as Caravaggio. From the moment his talent was discovered, he swiftly became the most famous painter of his time in Italy, as well as a

source of inspiration for hundreds of followers throughout Europe.

The Taking of Christ was painted by Caravaggio for the Roman Marquis Ciriaco Mattei at the end of 1602, when he was at the height of his fame. Breaking with the past, the artist offered a new visual rendering of the

narrative of the Gospels, reducing the space around the three-quarter-length figures and avoiding any description of the setting.

All emphasis is directed on the action perpetrated by Judas and the Temple guards on an overwhelmed Jesus, who offers no resistance to his destiny. The fleeing disciple in disarray on the left is St John the Evangelist. Only the

moon lights the scene: although the man at the far side is holding a lantern, it is in reality an ineffective source. In that man's features Caravaggio portrayed himself, at the age of thirty one, as a passive spectator of the

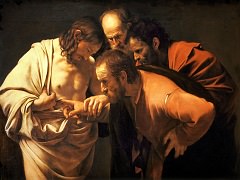

divine tragedy.The painting represents Jesus Christ being captured in the Garden of Gethsemane by soldiers who were led to him by one of his disciples, Judas Iscariot. Tempted by the promise of financial reward, Judas agreed to

identify his master by kissing him: "The one I shall kiss is the man; seize him and lead him away safely" (Mark 14:44). Caravaggio focuses on the culminating moment of Judas' betrayal, as he grasps Christ and delivers his

treacherous kiss. Christ accepts his fate with humility, his hands clasped in a gesture of faith, while the soldiers move in to capture him. At the center of the composition, the first soldier's cold shining armor contrasts with

the vulnerability of the defenseless Christ. He offers no resistance, but gives in to his persecutors' harsh and unjust treatment, his anguish conveyed by his furrowed brow and down-turned eyes. The image would have encouraged

viewers to follow Christ's example, to place forgiveness before revenge, and to engage in spiritual rather than physical combat. Caravaggio presents the scene as if it were a frozen moment, to which the over-crowded composition

and violent gestures contribute dramatic impact. This is further intensified by the strong lighting, which focuses attention on the expressions of the foreground figures. The contrasting faces of Jesus and Judas, both placed

against the blood-red drapery in the background, imbue the painting with great psychological depth. Likewise, the terrorized expression and gesture of the fleeing man, perhaps another of Christ's disciples, convey the emotional

intensity of the moment. The man carrying the lantern at the extreme right, who looks inquisitively over the soldiers' heads, has been interpreted as a self-portrait.