The Death of the Virgin, 1603 by Caravaggio

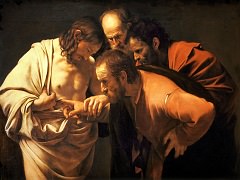

Traditionally the Transit of the Virgin, to which the chapel was dedicated, is depicted as a transcendental event - the Virgin usually makes some pious gesture, her soul is sometimes shown flying heavenward, and clouds of angels

often appear. Caravaggio, freed from the burden of doctrine imposed by The Madonna of the Grooms, presented the unrelieved sorrow of an ordinary mortal death. Mary lies on a kind of litter,

a poor woman, plainly dressed and barefoot, too weak to have crossed her hands in prayer and too worn even to welcome the release of death. The same Mary Magdalene who wept in The Entombment

huddles disconsolately beside her, and the apostles stand by, hushed and helpless. The young man kneeling must be Saint John the Beloved, and one of the grandfatherly figures Saint Peter. Otherwise, the mourners are not

identifiable as specific apostles.

This anonymity consolidates them into a group of grieving friends rather than distinct personalities who might distract the viewer from concentrating on the Virgin and the inescapable fact of physical death. The focus is on her:

she forms the only horizontal in the cluster of figures and is the only one who is not crowded by the rest; hers is the only body fully revealed, and her frailty and exhaustion contrast with the apostles' vitality, even though it

is subdued by their grief; and only she is fully illuminated. The light, softened by the atmosphere and by the handling of the pigment, fortifies the silent solemnity of the scene.

The emotional and physical starkness of the painting is unrelieved. The room is bare, stripped not only of rhetoric but also of extraneous detail. Caravaggio allows no hint of ritual, not even the customary sacramental censer and

candle, and only two touches of domesticity: the beautiful somber copper pan at the foot of the bier and the great red swag of drapery filling the space overhead.