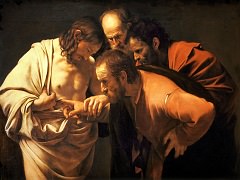

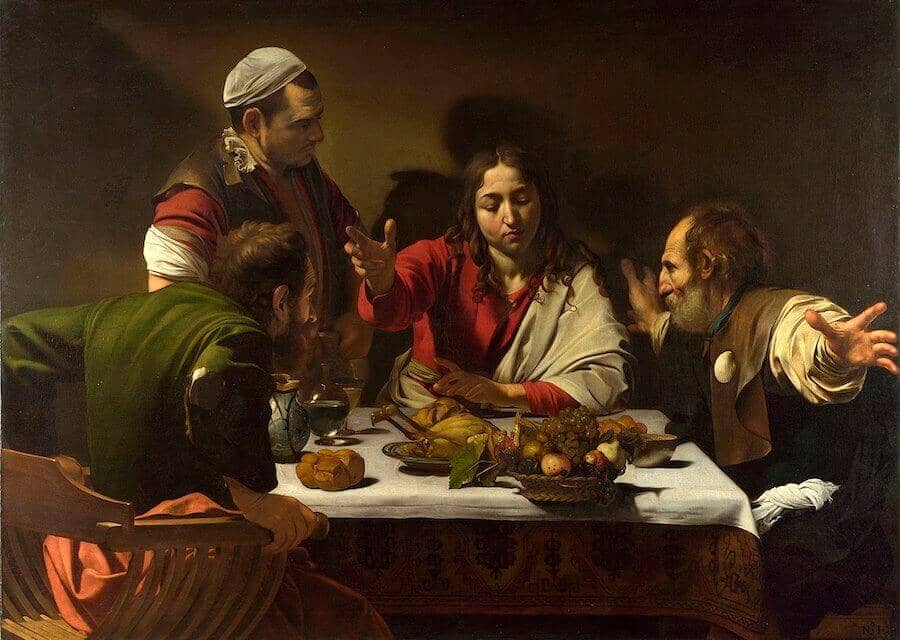

Supper at Emmaus, 1602 by Caravaggio

The Supper at Emmaus can be seen as an elaborate showpiece which seeks to develop to the full the dramatic potential of a group of figures seated round a table. But, unlike those in the more modest Cardsharpers and The Conversion of Saint Paul, the thoughts and feelings of the protagonists are conveyed through violent movement and expansive gestures. Even Jesus seems rather too conscious of the effect he is making in this flamboyant gathering of vernacular eloquence in which not even the basket of fruit can keep still.

Although the grandiose gesture of Christ himself is derived from that of Michelangelo's Christ in the Sistine Chapel's Last Judgment, one is aware of Caravaggio's dependence on the posing of models and of the way in which they are not altogether successfully integrated into the action - note for example, the Apostle on the right, whose over-large right hand adds to the feeling of an inadequate assimilation of individually observed details. This was exactly the kind of failing implied by Van Mander in Het Schilder-Boeck of 1604 and stated much more explicitly by Mancini in his Considerazioni sulla pittura. But despite these obvious faults, the picture remains a great achievement which, doubtless because of its illusionistic excesses, as well as its masterly chiaroscuro and succulent still-life details, was widely admired and copied during the seventeenth century. It was bought by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the passionate collector and nephew of Pope Paul V, sometime after his arrival in Rome in the summer of 1605, possibly from Ciriaco Mattei.

Tests made on cross-sections of pigment at the Detroit Institute of Arts by Meryl Johnson have been interpreted as showing that Caravaggio employed the unusual technique of applying a thin layer of tempera, 'wet-on-wet', over the oil paint in the area of the tablecloth. The effect of this is allegedly, as in the Detroit Conversion of the Magdalen, to produce an additional translucence in the white highlights. But the biological staining technique used in these tests would need to be supplemented by gas chromatographic analysis before more certain conclusions can be drawn. The National Gallery, London, now possesses the apparatus for gas chromatography but it will only be possible to take samples for analysis from damaged areas when the painting is again in need of restoration. It should be added that biological staining tests carried out at the National Gallery on a number of admittedly smaller cross-sections of pigment than those sent to Miss Johnson at Detroit have not produced any firm results. Although they indicate traces of protein, and in some instances strongly suggest the presence of egg tempera, it is not at all clear whether tempera was applied in the unusual 'wet-on-wet' manner which Miss Johnson has suggested. Apart from the more conventional mixed-media technique of applying tempera over a dry layer of oil paint, a number of other reasons could be advanced for the presence of protein in these samples. Miss Johnson's conclusions may be correct, but it would be well to treat them with caution for the time being.

The Supper at Emmaus is a popular subject matter among Old Masters, Rembrandt, for example, paints two version of The Supper at Emmaus