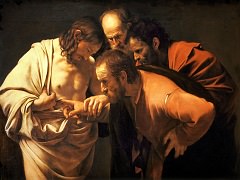

Supper at Emmaus, 1606 by Caravaggio

Probably this is the painting Supper at Emmaus, mentioned by Mancini as painted in the Campagna and sold to the Costa brothers. By 1624 it appears in an inventory of the Palazzo Patrizi in Rome, valued at three hundred scudi. It remained in the possession of the Patrizi family until its acquisition by the Brera in 1939.

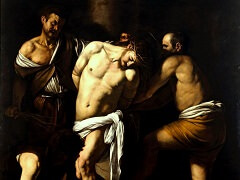

Caravaggio had mellowed during the four or five years intervening between the two versions of the subject, and this Emmaus has become sacramental in effect. Although its format is similar, details have changed: the aged serving woman added, the innkeeper moved to Christ's left, the still life reduced to a meager supper; and the poses and gestures have ceased to be bombastic. The colors, still varied in hue, have become less striking, the light softened, the atmosphere deepened, the fattura loosened and its glossiness dulled - as in The Death of the Virgin. These changes, none very drastic in itself, indicate a transformed conception of the subject.

Christ gives the cue. His physiognomy is no longer eccentric, and He is now bearded, as if Caravag¬gio had discarded the iconographic subtlety of the earlier clean-shaven Redeemer as too recondite to be relevant. Perhaps for the same reason the flask containing the symbolic wine is almost hidden behind the pitcher. Christ's head and upper torso form an equilateral triangle, giving Him calm, dignified stability. Instead of exhorting the apostles, He now speaks to them softly. His earlier energy has turned to spirituality; His physical presence has become sacred authority; and the emphasis is less on His miraculous reappearance than on His compassion. In fact, He is again incarnate, casting a shad¬ow on the innkeeper. Peter's dark right hand on the table almost touches the "whitened sepulcher" of His left, as if seeking the reassurance of physical contact. Christ, resurrected as He is, has still re¬turned to man as a wearied man.

Correspondingly, Cleophas, younger than before, and Peter, older and more haggard, have become less forceful, still surprised but more reverent. The innkeeper is older and worn. The coarseness of his large, spherical head contrasts with the refinement of Christ's, but his curiosity has turned to sympathy. The faded old woman might seem extraneous. Too battered by age, fatigued, and defeated by hard daily routine to see or to understand, she nonetheless belongs, even uncomprehendingly. She is an object of compassion, one of the mute and helpless meek of whom Caravaggio was increasingly aware.

It is a sad picture, drained of the dynamism of the earlier version, as if Caravaggio had come to re¬alize the tragic reality of the broken little band of Christ's followers and the impoverishment and hopelessness they felt without Him. The London Emmaus was no less sincere, but it was bold, its pro¬tagonists powerful, and its impact deliberately forceful. This painting is more withdrawn, the figures smaller in relation to the canvas and contained within it. Cleophas's hands do provide a bridge from our space to theirs, but the figures no longer burst out of the canvas. Psychologically they are too absorbed in their intimacy and the whole picture too restrained and sober to impose themselves on us.